We traveled to the O.H. Hinsdale Wave Research Facility at Oregon State University in the Summer of 2021, with the goal of studying the wave attenuation efficacy of an interlinked network of floating prototypes in a controlled laboratory environment. We wanted to figure out how well the prototypes could reduce the wave energy in the coastal ocean—both at the time of initial deployment, and after marine life had colonized the unit undersides.

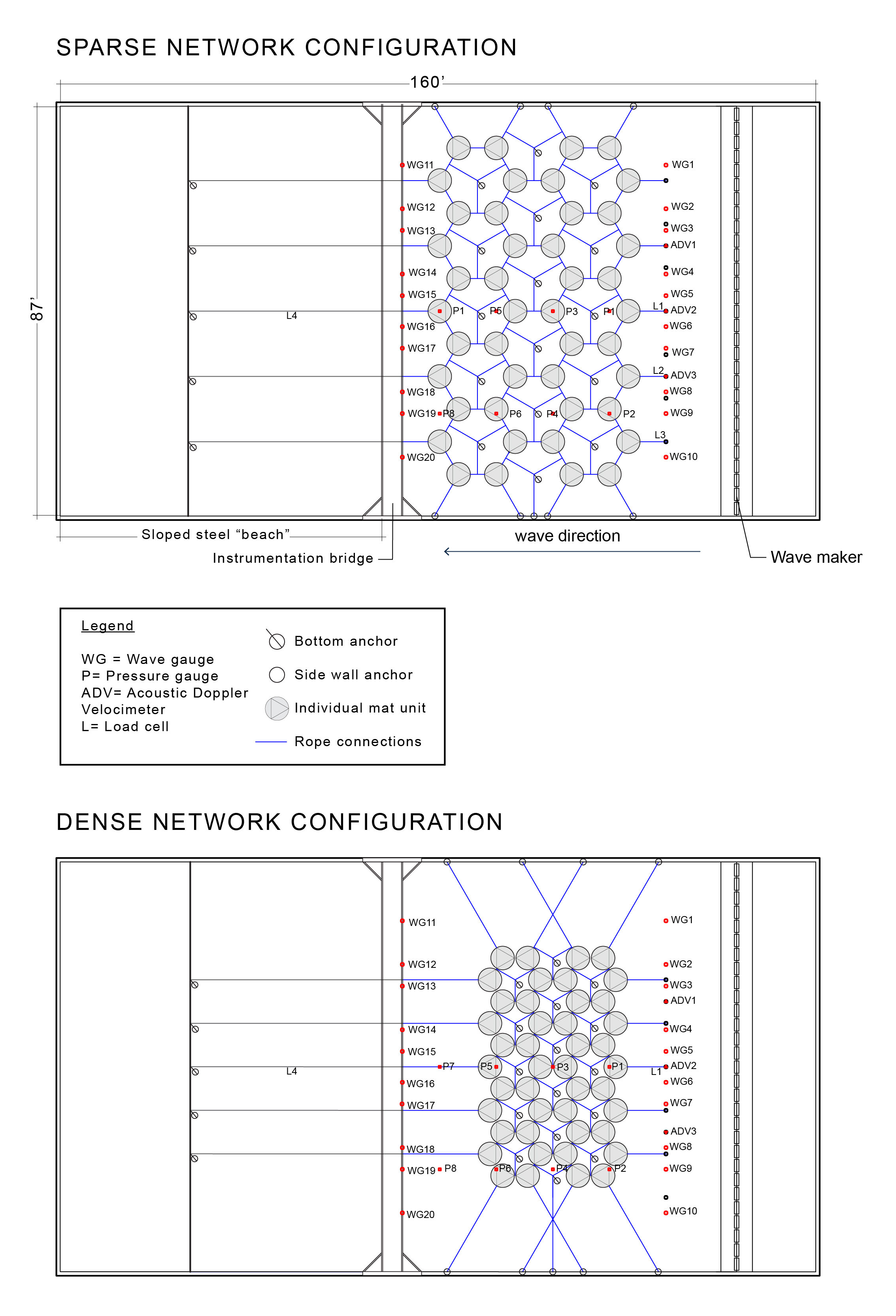

Like the tsunami pools in waterparks, the OSU directional wave basin laboratory facility is a large (160 foot long, 87 foot wide, 7 foot deep) water-filled basin that produces controlled waves of set periods and amplitudes. Instead of screaming children and tropical beverages, this wave tank facility hosts data collection systems and sensors that monitor wave height, water pressure, water velocity, tension forces, and other customizable parameters. The most relevant sensor array in our study were two sets of wave gauges, “landward” and “seaward” of our prototype network.

Set Up

To prepare for this experiment, we constructed 44 prototypes using laboratory materials such as canvas, foam, and wood waste. We chose these materials to closely match the size, mass, and roughness of our actual prototypes. We also included rainscreen mesh and bundled fabric to mimic salt marsh vegetation above the water and colonizing seaweed below, as we expected marine organisms would grow on the real-world prototypes that these units represented.

We deployed the 44 units in the wave tank and connected them together using reconfigurable ropes. The experiment consisted of 32 distinct trials with varied wave period, wave height, prototype network configuration, and vegetation density on each prototype.

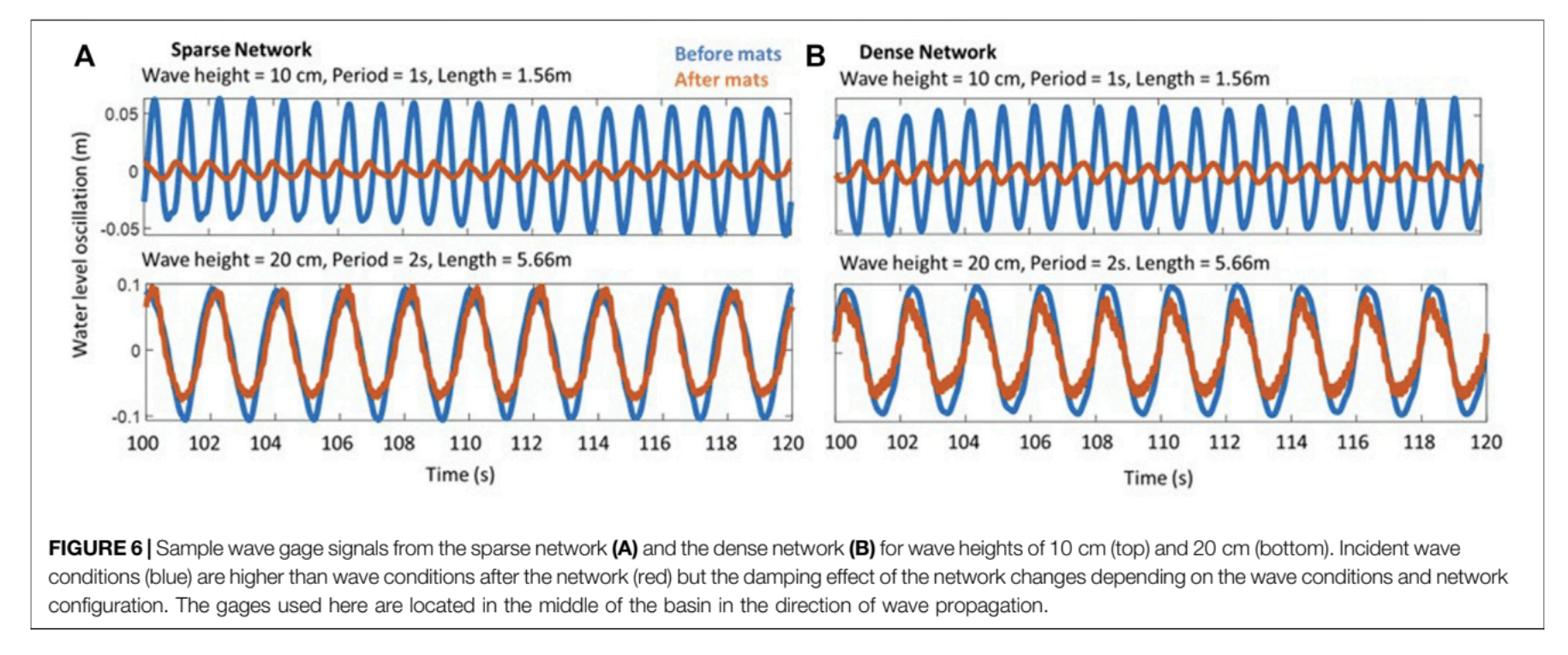

We looked at how the waves behaved landward and seaward of the network in the wave tank. The wave gauge sensors allowed us to collect data on how the prototypes, in a connected network formation, were affecting the shoreward wave conditions.

Small, short waves can be reduced by up to 90% of their original height. This effect is visible in the test shown in the animation. These waves are 1.5 meters long and 0.3 meters in height, or about the same as rough outer Boston Harbor conditions on a windy day.

Results

Through analyzing the data collected across the 32 trials, we determined that the wave attenuation of the prototypes is a function of the properties of the incoming waves. When the wavelength was shorter than the length of the prototype, the network was highly effective at attenuating waves. When the wave is longer than an individual prototype but shorter than the entire network, some amount of wave energy is dissipated. If the wave is longer than the entire network, however, the network rides along the wave and dissipation is negligible.

The function of the network configuration was tested but was not as sensitive to wave attenuation as it was to the incoming wavelength of the waves. Two configurations were tested: Sparse (prototypes 1 meter apart) and Dense (prototypes touching). It was found that there was not a significant difference in performance given variable spacing in the network. This finding, in addition to the results outlined in the paragraph above, lead to a hypothesis about wave reduction as a function of overall linear surface area of vegetation (in the direction parallel to wave movement).

The direct results demonstrated that a network can be effective against wavelengths equal to or smaller than the individual prototypes themselves. These trials and results have been significant to our team and provided a crucial step in our continued research and our goal of scaling up Nature-Based Infrastructure. See the full results published in Frontiers in Built Environment, “The Emerald Tutu: Floating Vegetated Canopies for Coastal Wave Attenuation”.