The Emerald Tutu has learned many lessons from navigating the complex, often burdensome permitting process for nature-based infrastructure projects. Drawing from hands-on experience in multiple municipalities, we highlight the local, relationship-based nature of permitting, the structural barriers posed by outdated regulations, and recent policy shifts aimed at streamlining restoration-focused work. We also highlight our funding resources and key partner groups that are shaping the future of ecological restoration and coastal protection across the region.

NOTES ON PERMITTING

Our site-based research work and our advocacy activities in scientific and government communities have given us a unique view into the permitting and regulatory mechanisms applicable to Nature-Based Infrastructure.

Permitting is inherently local and jurisdictional, and varies considerably from town to town. There are always federal, state, and local regulations at play, but regulatory culture often reflects a more common local attitude to the values of development, industry, and restoration. This culture—inherently based in shared human understanding—defines the protocols and practices of permitting. Not the other way around.

In our work in the towns of Lynn, MA, Quincy, MA, and Stonington, CT, all permitting was accomplished by email and phone communication with local authorities. In different ways, those with an interest in marine issues—harbormasters, conservation agents, town planners, and even local business leaders—typically share responsibility and oversight on coastal and marine issues. We found that these people generally support efforts pertaining to restoration, nature-based infrastructure, and coastal protection, and helped us through the process.

In the City of Boston, we have navigated formal Conservation Commission permit proceedings for both of our research sites in East Boston. These processes are painful and time-consuming, so much so that most projects hire consultants for it, but we managed to get through it ourselves. Abutters need to be canvassed, multiple state and city agencies must be formally notified in the correct order, and hard copies of all documents and revisions must be submitted in duplicate. There are filing fees for various components, and certified translations required for certain documents. These measures, which originally intended to make the process more public and standardized, actually create significant barriers and cost increases for restoration and coastal resilience projects; it is not atypical for 30% of a project budget to go toward permitting costs, a serious burden on cost efficacy for restoration projects.

In general, the most restrictive environmental regulations were written under the assumption that the applicant is developing infrastructure/assets with a profit or use motive. The regulations attempt to quantify “impacts”: possible disturbances to a variety of environmental resources, ranging from groundwater to habitat to expected traffic changes. The individuals involved from the various state and city agencies encourage best practices along the way, and expect the applicant to appreciate their advice and the industry standards. The ultimate commission hearing is usually quiet and uncontentious; projects are typically approved and it’s clear that the more fundamental decisions are made elsewhere.

Our permitted areas in East Boston are the Floating Frame at the Piers Park waterfront and the intertidal area at 102 Border Street. Both of these sites were permitted in a way that allows many prototypes and experimental apparati to be deployed and adjusted there within certain limits, so that (in both cases) we are able to conduct controlled trials and observe our prototypes frequently and closely as they grow and change over time.

Large-scale nature-based infrastructure has the same burdens of permitting as other large infrastructure projects. The areas that our research work targets—the swash zone, intertidal zone, and nearshore zone—are tightly regulated resource areas. Federal waters, including the major dredged shipping channels within urban harbors, are of course reserved for navigation, but all other parts of urban harbors and coasts are under local jurisdiction and subject to the regulatory permitting and long-term management of the municipality. In other words, it’s up to us, as denizens of a City threatened by rising tides, to regulate and formulate the protective infrastructure suited for our coasts.

Over the last few years, regulators have come to understand that Nature-Based Infrastructure faces undue hurdles of permitting. Specifically, in Massachusetts, this has been addressed by legislative action which took effect in early 2023, creating a streamlined permitting process for ecological restoration projects. Creating this pathway effectively allows projects like ours, whose fundamental goal is to restore ecosystems, to skip the full Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act Office (MEPA) review process for environmental impact assessment. For non-restoration projects in wetland resource areas, this process can add 2-4 years to the project timeline.

We live with the generational legacy of 1970s environmental activism and the muscular regulations that resulted, which were generally intended to protect natural resources from being ravaged for industry, infrastructure, and development. Fifty years later, these are shifting to allow environmental projects to proceed more easily, and respond to the existential threat of coastal climate change.

NOTES ON FUNDING

We have received various grant funding supporting our R&D and our “Green Job” training program, and various accolades that helped us along the way:

– Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) ‘Climate Changed’ Competition, First Place, 2018

– American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) Innovation award, 2019

– National Science Foundation (NSF) SBIR Phase I grant, 2021-2022

– National Science Foundation (NSF) SBIR Phase II grant, 2023-2025

– National Science Foundation (NSF) CIVIC Innovation grant, 2024

– MassBays National Estuary Partnership, Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) funding, 2025

REGIONAL PLANNING DISCOURSE

From 2017 to 2022, the City of Boston conducted neighborhood-by-neighborhood planning exercises to study coastal climate risks and propose possible local upgrades and solutions. They began with East Boston, the environmental justice (EJ) neighborhood that is affected first and worst by coastal flooding and other climate hazards, and continued to recommend a fine-grain responsive approach to coastal resilience that designs with “Equity, Adaptability, and Ecological Restoration” as principal goals.

In 2016-2019, a group of business leaders and public sector volunteers convened as the “Boston Harbor Regional Storm Surge Working Group,” proposing a colossal seawall and seagate system that would stretch 5 miles across the mouth of Boston Harbor. Led by former MA senator William Golden, they retained engineering firm Tighe & Bond to illustrate their concept, and argued that although it would be costly (estimated at $8-12 billion) it would save the City and surrounding cities from future coastal flooding.

A broad consortium of scientists and consultants rebutted, publishing in 2018 the Feasibility of Harbor-wide Barrier Systems report. They concluded that such massive infrastructure would harm harbor ecosystems and water quality, would take 25+ years to function as designed, and would require large swaths of beach in Hull, the harbor islands, and Winthrop to be converted to elevated concrete walls and dikes. They suggested instead, to refer to the then-new East Boston Climate Ready Boston report, with a concluding note about a fine-grained, localized approach to adaptation that “can contribute to neighborhoods through co-benefits in a way that a harbor-wide barrier cannot.”

Why spend $8-12 billion to preserve the city as it is? We live among the abandoned infrastructural relics and haphazard halfhearted aspirations of previous generations. The “city on a hill” is broken and unjust, and creating an external device to save it will only exacerbate the fundamental problems of economic and climate inequality.

RELATED GROUPS

Mass ECAN Nature Based Solutions (NBS) Working Group

The History and Future of the Hess Site

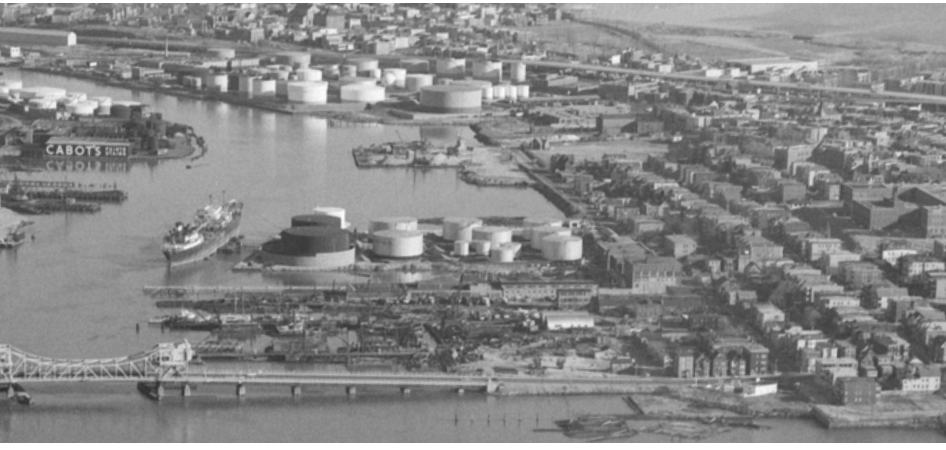

Nature is taking over 8 acres in the middle of the city. The abandoned, contaminated waterfront parcel—the largest undeveloped property owned by the City—sits waiting as the complexities of post-industrial land use scramble all developer formulas. Tree roots grow through the cracked concrete slabs left behind after gas tanks were removed, and birds hunt and nest in the freshwater wetlands. Groundhogs, skunks, and a few intrepid felines scurry through the tall grass. The area is fenced off, but people still find their way in.

Meanwhile, the neighborhood faces more and more extreme heat and coastal flooding. The Hess Site is a reminder of the long-term legacy of industrial and fossil fuel uses in low-income neighborhoods. With no easy answer to the puzzle, the site is neglected and left to sit.

Even in its wild state, it shows many signs of life—and maybe, a chance for change.

The Hess Site

“The Hess Site,” located on Condor Street in East Boston is a former oil storage facility and oil tanker transfer terminal on leveled and filled historical tidelands with seawalls at site edges. The site is 8.34 acres total: ~7.34 acres of upland area and ~1 acre of water sheet. There are heavy steel breasting dolphins and a gangway at the site’s water sheet interface with the Chelsea Creek, a federal navigable fairway leading to Boston Harbor. It is situated within a Massachusetts Designated Port Area (DPA) and has a deeded AUL based on historic oil (volatile and lead) pollution from the Amerada Hess Corporation’s most recent use of the site for oil loading and storage. Bulk chemicals were removed in 1979, and the tanks themselves were removed in 1998.

The AUL, which was tailor-made to the site and its pollutants in 2007, disallows certain site uses such as residences, schools, daycare, or “other such use at which a child’s regular presence is likely,” and disallows the “growing of fruits and vegetables for human consumption.” Certain uses, such as commercial and industrial, are allowed, but any building for human occupancy built on the site would require “a vapor barrier with a passive ventilation system” beneath the foundation to prevent volatiles from accumulating in interior spaces.

The site is also within the FEMA Flood Hazard Zone AE, indicating that the area has at least a 1%-annual-chance of being flooded, but where wave heights are less than 3 feet. There are strict requirements for equipment, floor levels, and living spaces in AE Zone buildings, and FEMA strictly controls fill in floodways. These restrictions severely limit allowable and viable uses of the site.

The Chapter 91 Presumptive Line (C91PL) crosses the South side of the site, and historic maps as early as 1852 Boston McIntyre and 1836 East Boston Pendleton show a formally similar line as the natural coastline shape in this location. The DPA limits site development and use to “marine industrial water-dependent uses,” and applies to this site on the coastal side of the C91PL.

Our Chance for Change

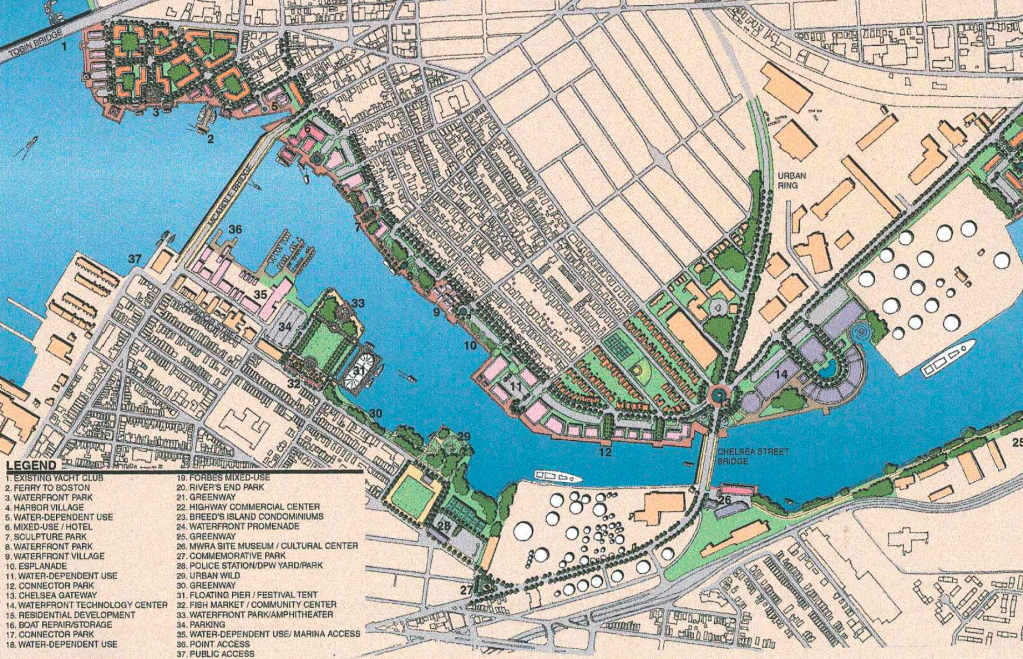

The “Blue-Green Nursery for Nature-Based Infrastructure” gracefully satisfies the labyrinth of constraints that the Hess Site poses, and would be a benefit, rather than a detriment, to its neighbors. The vision is a zero-emissions, fertilizer-free, publicly accessible nursery for the mass production of native coastal plants to be used in Nature-Based Infrastructure (NBI) projects for coastal resilience and ecosystem restoration across the Northeast region. The nursery would be composed of a series of high tunnel greenhouses, outdoor growing and plant storage zones, rainwater collection and irrigation systems, and other farm structures. The seedlings and plants would be sold to green infrastructure projects focused on protecting coastlines, improving water quality, and benefiting neighborhoods and habitats for generations to come.

There are no enclosed spaces for human occupancy, the site use is water-dependent marine industrial, and any structures for plant growth will not be catastrophically affected by coastal floods as they are regularly irrigated with saltwater. This project will move toward fulfilling the required public waterfront access for “fishing, fowling, and navigation” as dictated by Massachusetts General Law (MGL) Chapter 91 regulations and will create a free, open-access amenity for East Boston. The other compatible community uses of the site, many similar to their present uses, will make the space feel like an improved home-base for several of the most impactful East Boston community non-profit and advocacy organizations.

When local activists were dealing with the site ownership, pollution, and litigation in the late 1990s, they produced a comprehensive planning document. This report is addressed to a future generation, and it vociferously calls for community-driven planning and this genre of community site use (The Hess Site Re-Use Planning Project, December 15, 2001). We intend to fulfill their visions for the site as a common-use amenity for generations to come. Help us make our dreams and ambitions happen and reach out to learn more!