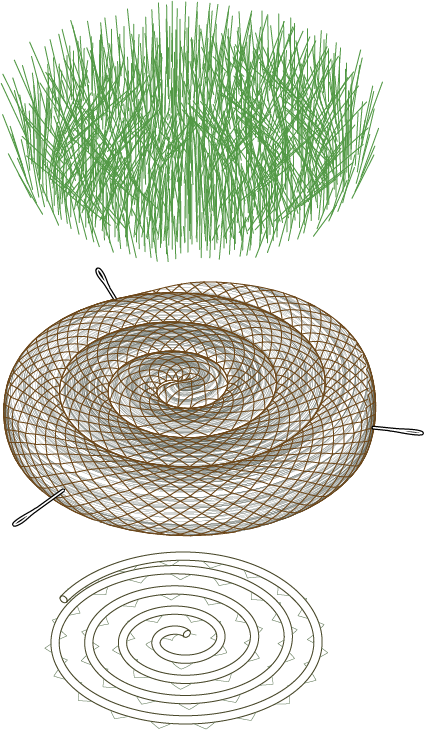

The Spiral Net Prototype style is the culmination of multiple years of prototyping, responding to the successes and failures of previous trials and iterations, and is our most successful family of prototypes. The tight spiral wraps hold the biomass substrate tightly enough so that it does not shift with the rhythmic motion of the ocean nor stratify from uneven buoyancy. It consists of a spiraled tube enclosure of coconut fiber netting filled with dead Phragmites australis reeds, that is stuffed, rolled, and lashed into a dense disc form.

How It’s Made

The Spiral Net Prototype, like many of our unit designs, is prefabricated and can be built and stored in advance of launch.

Harvested Phragmites reeds are laid atop a 40 foot long flexible sheet of plastic, taking care to spread and distribute the individual reed pieces so there is always adequate overlap in their length. This ensures a uniform diameter log of material, with no inconsistencies where kinks or tears could form.

The sides of the plastic sheet are curled in to encapsulate the biomass, and a long coconut fiber tube of netting slides easily around the outside of it.

As the plastic sheeting is pulled out from one end, the coconut fiber tube tightens around the inner biomass, creating a long continuous log of Phragmites encased in coconut fiber netting.

This long, flexible log is then wound into a spiral much like a hay bale roll, while the three-rope frictional tension yoke attachment is threaded through each wrap. The spiral is laced together with thin nylon string, which seals each wrap to the next, and tightens it into a compact disc. This disc is the fundamental substrate assembly for our floating units: it is a dense but flat bundle of biomass that holds its shape well over time and is 99+% biomass.

We have tried several approaches for adding marine foam buoyancy to this spiraled biomass assembly. In general, the best approach to added buoyancy is a well-distributed layer affixed underneath. The simplest and most successful approach used a 1.5 inch thick unreinforced sheet of polystyrene laminated to the bottom of the spiral disc substrate.

The other approaches to buoyancy were more cumbersome and more likely to cause stratification or tearing due to uneven buoyancy force distribution. See the “Failures” section below to learn about some of the less successful buoyancy approaches.

As with all our prototypes, the final element is the living component, the Spartina alterniflora marsh grass. Since the spiral disc is premade, it typically has the marsh grass plants inserted just before being transported to a coastal deployment location to ensure they stay moist and survive. The various concentric spaces between the spiral wraps work well to tightly hold plant plugs as the roots grow.

This diagram shows the components that go into a single Spiral Net style prototype and how they attach together. In this particular version, buoyancy is represented as a flexible spiral layer—we actually found this buoyancy approach to be inadequate for long-term saltwater submersion, so more recent versions of the Spiral Net prototype use a sheet of marine foam instead.

Deployment Locations

Three prototypes with flat polystyrene foam buoyancy sheets were deployed in Lynn Harbor in an interconnected triangle formation with three external anchor points. The purpose was to evaluate their ability to withstand significant ocean wave exposure and test out a triangular (non-rotating) mooring system.

Several other prototypes of this style were deployed at Piers Park waterfront where their three yoke attachment points were tied to the floating frame, rather than directly to moorings.

Two more prototypes were attached to each other and deployed at the East Boston Shipyard Graving Dock and secured by ropes tied to chains at the wharf edges. The chain and rope combination allowed for the units to rise and fall with the large tidal range.

At the Neponset River two units were deployed individually, each with its own buoy and anchor connected by a single rope.

Successes & Failures

Successes:

- The spiral formation proved to be the strongest and tightest shape, holding the biomass substrate steady through storm events as well as continuous wave action. Due to the circular overall wrapped form and curved outer shape, there was no possibility of exposed reed ends fragmenting or fraying, and the seedling plugs of Spartina alterniflora held tightly within it.

- The flat disc shape maintains the ideal immersion and wetness for Spartina alterniflora to thrive over its full top surface. This was the first prototype that enabled some Spartina plants to survive a winter floating in Boston Harbor and regrow on their own in the spring.

Failures:

- The spiral prototype and methodology had the most success so we wanted to test multiple variations by adjusting other elements: buoyancy, mooring/anchoring, etc. The specific failures of each are described below.

Failures of Specific Prototype Variations:

Polyethylene (4” diameter cylindrical tubes) inside the spiral tube at its core

- The prototypes with polyethylene inside the spiral tube loosened over time with buoyancy forces, and the foam eventually became dislodged and forced upward through the other substrate materials. The separation and stratification of the materials deformed the entire assembly. Some prototypes stretched from about 1 foot in height to around 4 feet, and some of the coconut fiber netting began to tear.

Polyethylene (1” diameter cylindrical tube) lashed at the seams on the underside of the spiral

- Two prototypes with polyethylene lashed on the bottom survived the winter and in the early spring were still floating but sitting lower in the water due to (1) the foam degrading, (2) the Phragmites becoming increasingly heavier due to saturation, (3) as the weather became warmer, algae colonizing the top of the prototypes, and (4) uneven tensions from the attachment system in the Graving Dock. The spiral mats became imbalanced and lopsided due to those four compounding factors, causing the prototypes to flip over and arrange themselves with buoyancy on top and biomass towards the harbor floor.

- Two other prototypes with the same foam method located at the Neponset River were more of a mystery. Monitoring was less frequent, and by springtime they had disappeared. It’s possible that some of the same factors were at play. These units were identical, but their attachment method was distinct with only one connection point (like a boat on a mooring). It is possible that they sank and became covered in sediment, or that the rope was severed and they floated away.

- One other identical prototype, located in the Floating Frame, was more successful and long-lasting. It began to sit lower in the water over time, but stayed solid and flat. This unit was attached with 3 lateral connections, which prevented it from flipping or becoming lopsided.